Teaching Marcel Moyse’s Tone Development Through Interpretation

This is a go-to technique in my flute-teaching to teach how to play with a modern, multi-coloured, expressive sound.

There is an actual book that this method uses, Marcel Moyse’s Tone Development Through Interpretation, which I studied for a long time as a student.

But I don’t teach it just using the melodies written in the Moyse’s book. I learnt gradually (maybe glacially) that there’s no magic in just those tunes, many of which are now somewhat obscure. It’s really the approach that we can learn from; the repeated close listening, the acute study of tone colour, character and direction, how to carry and characterise tunes, the transposition of originals to then deal with the difficulties posed by transposition into different keys.

Also, just having the love for the tunes themselves is vital – I find they have to be personally really meaningful for me to spend enough time on them to really benefit. Fewer tunes really mean as much to me in the actual Tone Development book as other tunes I’ve collected.

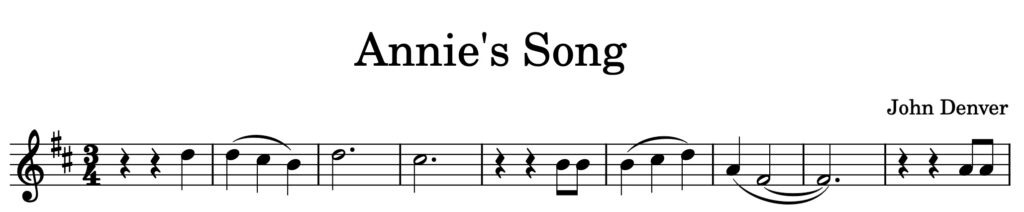

I often start with an actual flute tune (or one at least played on the flute) such as James Galway’s rendition of Annie’s Song: a great recording, something I’ve loved listening to for decades (I totally lack hedonistic response).

I love this tune because it’s so simple – short phrases, limited range, small jumps, easy to remember. Nothing not to like.

What to focus on? Tone colour and intensity (the most obvious “tone development” bit of it), imitating Galway’s vibrato, his quasi-portamento legato from one note to another, the sense of direction and intent he imparts in the phrases. Often times it’s the degree to which the tone/dynamic is developed that is the revelation.

My students and I do this all from ear – just listening and remembering. It’s somewhat disabling of your listening abilities to be reading music and easy to get into a reflexive, this-is-how-I-always-play-the-flute groove without questioning whether you’re reproducing really what you hear.

Later I branch out to mainly non-flute tunes – lots of voice and strings but also other woodwinds. This is harder of course, but we can learn even more, especially from strings and singers with their hugely wide expressive range. And to be totally frank, most great instrumentalists would have the drop on even great flute-players in terms of expressive range.